France’s National Front had a disappointing Sunday, with early returns showing it had failed to capture any region in elections. Still, its strength is growing … and this does not come as a surprise to the French.

France’s National Front had a disappointing Sunday, with early returns showing it had failed to capture any region in elections. Still, its strength is growing … and this does not come as a surprise to the French.

France’s mainstream national parties, the Socialists and Nicolas Sarkozy’s newly re-branded right-wing party Les Républicains, only have themselves to blame for this situation — Le Pen will keep luring French voters from both the right and the left, until the mainstream parties react. Until then, it will remain the only drinker in an open bar.

Since the 1970s, French political discourse has been warped by a strange set of political taboos. A case in point: after the massacres at the Charlie Hebdo office and the Hyper Cacher grocery store last January, all members of France’s National Assembly broke out into a spontaneous Marseillaise. It was the first time all elected officials have sung the national anthem there since 1918. Despite France’s strong sense of nationhood, expressing nationalist sentiment is looked upon with suspicion by the political class and the media.

This is France’s peculiar, and dangerous, brand of political correctness. Though the French can be quick to deride Americans for political correctness, France’s traditional parties are unable to talk about fundamental issues like immigration, Europe and patriotism. As a result, the issues have become a blind spot for France’s political class and media.

The only chance France has for not succumbing to the far right folly is to get over its taboos and start talking about the issues that matter to the French

It is next to impossible for a mainstream French politician, especially on the left, to broach any of these subjects without being accused of having far-right sympathies. When politicians do talk about them, they do so in private to avoid scandals. When she was a presidential candidate in 2007, Socialist Leader Ségolène Royal waved the flag and sang the national anthem at political rallies, and talked of her love for France. France’s left criticized her for it, which contributed to her loss.

There are good reasons why these taboos exist. Historically, religion, ethnicity and extreme nationalism have been at the core of many of Europe’s wars. The French rather blindly assumed that their official policy of assimilation would somehow erase that and that everyone would benefit. The European Union, founded to maintain peace on the continent, was cast in the same light and became irreproachable in France’s public discourse.

The problem is, France’s mainstream political parties went on to become prisoners of their own discourse, forgetting to speak for the French who suffer from ill-considered, or ill-applied, European Union policies. They also forgot to stand up for the French, for whom the principles of the republic failed: victims of chronic unemployment, violence and members of a permanent immigrant underclass.

The National Front has increased its support because it’s the party that provides answers — even though they are bad ones — to problems France’s other parties barely acknowledge. But for those who fear the rise of the National Front, the results of the regional elections also carry hope.

If the attacks in Paris had any effect on the regional elections, it was to buttress the Socialists. President François Hollande’s firm stance in the war against terrorism and his moves to increase national security have boosted his popularity sharply to 50 per cent — his highest score since he was elected in 2012.

The regional elections were the last until France’s presidential elections in April 2017. For the next 18 months, French politics, particularly on the left, will be a three-way tug-of-war, as the two mainstream parties try to steal some of Le Pen’s thunder.

Sarkozy’s Les Républicains, being on the right, are desperately looking for the magic formula that will lure voters while steering clear of the extreme right. On the left, the only Socialist who dares to shake the party out of its political correctness is Prime Minister Manuel Valls, who was appointed by President Hollande in April 2014 to find a new course. But hardcore Socialists views Valls’ positions with suspicion and Valls is more popular outside of his party than inside.

The only chance France has for not succumbing to the far right folly is to get over its taboos and start talking about the issues that matter to the French.

National Post

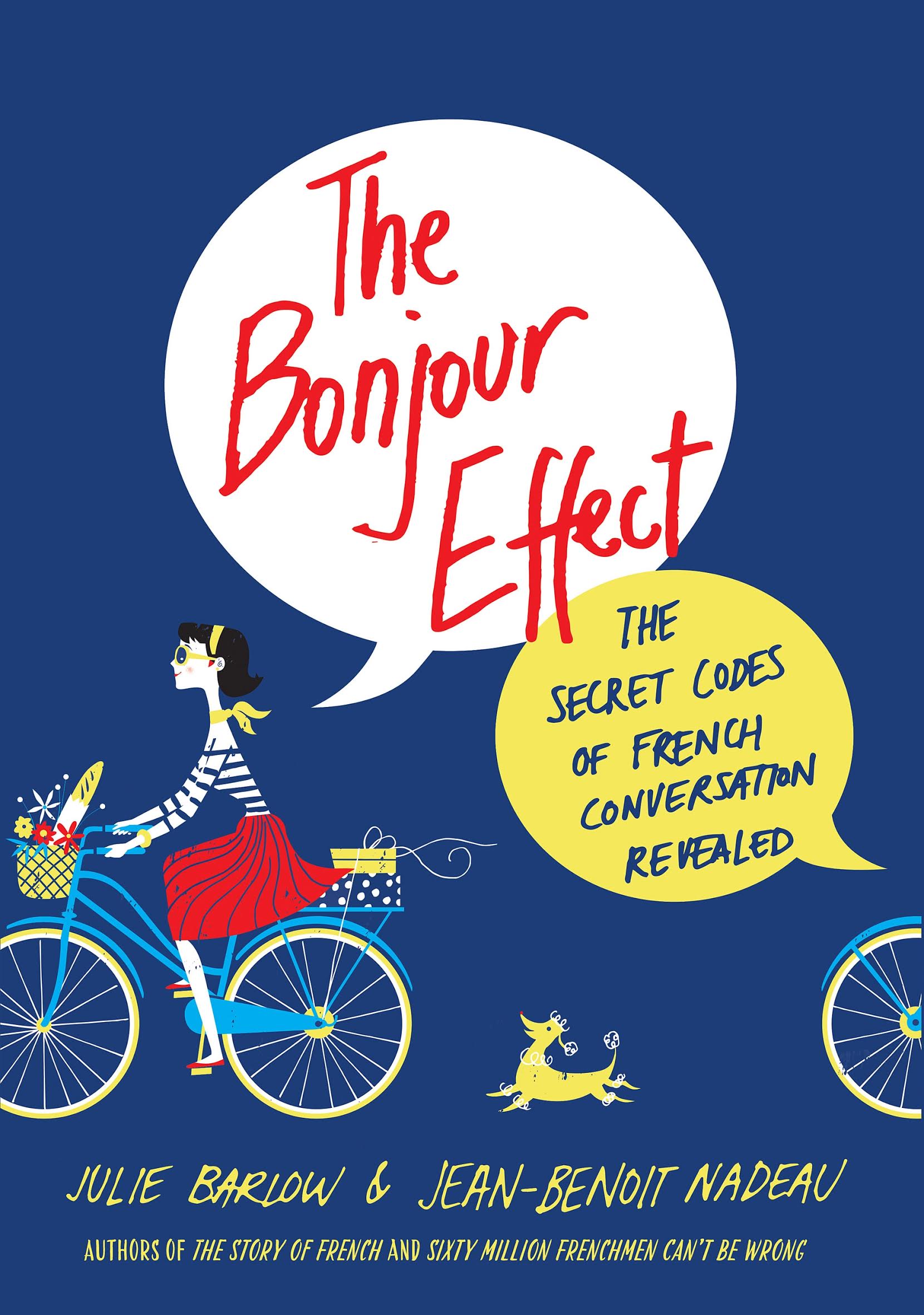

Julie Barlow and Jean-Benoît Nadeau are the authors of Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong. Their new book The Bonjour Effect: The Secret Codes of French Conversation Revealed will be released in April 2016.