By Jean-Benoît Nadeau & Julie Barlow

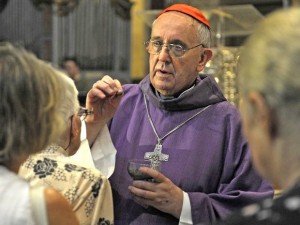

The new pope Francis is an Argentine of Italian descent and a Jesuit to boot – all of which highlights some fascinating, and even contradictory, aspects of the story of Spanish in Latin America.

Our book, the Story of Spanish, in a way, explains why the first Latin American Pope is from Argentina.

With at least 40% of believers, and closer to 50% if you include North Americans, the Catholic Church’s center of gravity is clearly west of the Atlantic Ocean.

This is largely due to the work of Spanish missionaries. Curiously, Spanish missionaries had tremendous success in the New World because the Church succeeded in creating a brand of syncretic Catholicism that integrated many features of native cultures. In addition, the Church protected the natives against abuse from conquistadores and colonial powers.

Yet, this success initially worked against the Spanish language. In the centuries following the conquest, the Church actually preached in and taught certain native languages: Nahuatl in Mexico, Quechua in Peru, and Guarani in the South Cone. This practice, of course, stalled the progress of Spanish in the Americas for 250 years.

A Jesuit

The Jesuits played a key role in the history of the Spanish language. The Church only reconsidered its position on native languages in the middle of the 18th century, when it banned the Jesuit order in 1767 and expelled thousands of Jesuits from the New World.

Why were the Jesuits banned? In a way, they were victims of their own success. They were very effective missionaries who had developed their own power networks from the Rio Grande to Patagonia. That made the Spanish Crown nervous. In Paraguay, Jesuits ran 40 semi-independent reducciones (missions) with up to 150,000 believers, where no one spoke Spanish, no one was enslaved, and no money exchanged hands—the whole system ran on barter. This “last outpost of utopia in the New World,” as it was called, inspired the film The Mission.

The expulsion of the Jesuits had many repercussions on the status of the Spanish language.

Firstly, it backfired, politically speaking. The Jesuits were the continent’s most enlightened clergy, who taught a liberal curriculum and “served the Spanish American elites a big dose of Descartes and Leibniz,” as the Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes wrote. In the colonies, their expulsion was felt as a terrible loss, and sparked the first flames of the Independence Movement in Latin America.

Additionally, the expulsion of the Jesuits shattered the last institutional and protective barriers for native cultures. The Jesuits had spent years learning local languages, and were impossible to replace quickly. When they were replaced, it was by Spanish-speaking priests.

Finally, Jesuit writings (often written in Rome, where many Jesuits ended up) are among the earliest reflections on a distinct American social identity, different from that of Spain, which would also add fuel to the 19th century wars of independence.

Argentine and Italian

The fact that most Latin Americans are proud of having an Argentine pope speaks volumes about the unifying power of language and faith. Why? Historically, Argentines have always considered themselves slightly “apart” from the rest of the continent.

Carlos Fuentes joked in his 1969 essay La nueva novela hispanoamericana (The New Spanish American Novel) that “Mexicans descend from the Aztecs, Peruvians from the Incas, and Argentines from the ship.” Fuentes was referring to the massive immigration of Europeans to Argentina.

With a population of only 300,000 in 1856, Argentina attracted more than 6.5 million immigrants by 1936. As an immigrant destination, Argentina was second only to the United States (34 million) and well ahead of Canada (5.5 million) and even Brazil (4.4 million). As a result, Argentina’s population inflated to 14 million by 1939. It was now closer to Mexico’s population of 19 million.

Oddly, such massive immigration had relatively little impact on the country’s culture or language. 80% of Argentina’s 6.5 million immigrants came from Italy, Spain and France, countries with Latin-based languages that assimilated rapidly. Argentina further encouraged linguistic assimilation when it introduced mandatory schooling in 1884 and military service in 1902.

It is no coincidence that the European-dominated conclave of cardinals chose a pope who “descends from the ship”: Argentina is by far the most European country of the whole continent.

More information about Argentina, the Church and missionaries can be found in our new book, The Story of Spanish, to be released in May 2013, St. Martin’s Press.

More information about Argentina, the Church and missionaries can be found in our new book, The Story of Spanish, to be released in May 2013, St. Martin’s Press.